In 1885, the MLB didn’t exist yet; initially only the National League existed. The NL wasn’t the only league in America, but it was the most popular one.

The Chicago White Stockings and the New York Giants were the two best teams in the league. Players, however, weren’t happy. The reserve clause was created in 1879 and gave owners unlimited control over their players.

There was no free agency, there were no salary negotiations, there were no players with power. If players didn’t like their salary, tough. If they wanted to leave their team for another, they couldn’t. If they wanted more money and wouldn’t play under their current salary, they weren’t going to play another game. Owners owned their players.

1885 was a bad year for players. That year the NL instituted a salary cap which capped their salary at $2,000 a year. The salary cap has since been abolished, technically, but there is a luxury tax for ball clubs that act as a sort of salary cap. Hall of Famer Michael “King” Kelly had to get a job in the offseason to make ends meet. He hit .388 in 1886 and is a career .307 hitter, yet he still had to work multiple jobs, something that is unimaginable now.

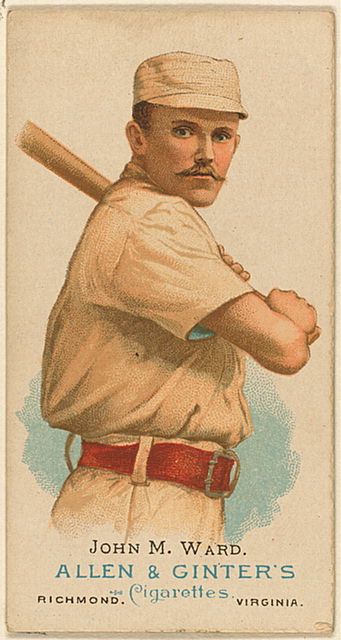

After the salary cap was instituted, players were outraged. They banded together to create the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players. The “Brotherhood” started with just 9 players with New York Giants player John Ward (a law graduate) serving as President.

The Brotherhood created a relief committee to help injured players still get money as they weren’t paid if they didn’t play, which enticed many other players to join the Brotherhood. The National League didn’t recognize the union until they agreed to have a meeting with them in 1887, but it didn’t go well.

In 1890, Ward and the union came up with a plan to revise the reserve clause. They proposed a reserve clause that allowed players to leave the team they played for after “x” amount of years. The NL didn’t want any part of that, so they struck down the proposal, dealing a big blow to the relatively new union.

The NL had a monopoly for many on professional baseball for many years, but in 1900, Ban Johnson created the American League. His plan to create a rival for the NL was better than the Players League was a decade earlier; he put teams in cities already occupied by the NL. In June of 1900, veteran catcher Chief Zimmer became president of the Players Protective Association, or PPA. Zimmer didn’t have a background in law, so they hired Harry Taylor.

The AL wanted to get players who were unhappy in the NL so the league didn’t institute a reserve clause. After that guarantee, 60% of the players in the AL had played in the NL.

Before the 1903 season, the AL “signed the National Agreement” and the first World Series was played between the two leagues. After 9 years of the two leagues playing nice, the players sought to create a new union. The Fraternity of Professional Baseball Players of America was formed in 1912, and former player Dave Fultz served as president. Fultz, however, wasn’t the most popular with the players because he didn’t like using the term “union” and wasn’t really interested in the players’ complaints. He did get teams to pay for players’ uniforms and change the color of the outfield walls to make the balls easier to see, but the Fraternity was overshadowed by a new problem.

The Federal League declared themselves a major league in 1914. The NL and AL sued them in 1915 for interfering in their operations. A historic lawsuit ensued that year: Federal Baseball Club v. National League. The Supreme Court ruled the Sherman Antitrust Act didn’t apply to the MLB, so the MLB was exempt from the antitrust act, a decision that affects players to this day.

After the Supreme Court dealt a major blow to players, they didn’t bother to start another union again until 1946. Many players, like Yogi Berra, Joe DiMaggio, and Ted Williams, just to name a few, returned home from Europe. A lawyer based in Boston named Robert Murphy started the American Baseball Guild after hearing about the players unrest in an expanded league.

He knew teams had to strike to be taken seriously, so Murphy focused on the Pittsburgh Pirates because the town was full of union workers. Before he called on the Pirates to strike in June, he made a list of demands to the league. He wanted a minimum salary for players ($7,500), arbitration to be available to players in a wage dispute, players to receive 50% of the purchase price if their contract is sold to another team, no salary cap, bonuses and insurance to be offered in contracts, and that contracts couldn’t be “one sided.”

Again, the demands wouldn’t be taken seriously if teams didn’t strike, so he called on the Pirates to do so. On June 7, in a players only meeting the players needed a supermajority to go on strike. Of the 36 players they needed 24 players to vote yes, only 20 voted yes to strike. They went on to play, winning 10-5, but they were heavily booed by the union workers in attendance. After the game, third basemen Lee Handley said, “We played a dirty trick on Murphy. We let him down, and I was one of those who did it.”

After the failed strike attempt, Murphy and the union faded, but the MLB did eventually cave on some of their demands.

They instituted a minimum salary of 5,500 dollars, a pension plan, “the ability for one elected player representative from each league to appear before them to discuss issues and grievances,” and spring trading per diem.

Later, Murphy said players took an “apple” but “could have had an orchard.” The MLB ruled over their players for over another 20 years, but then came Marvin Miller, who would change the MLB and sports unions forever.